So it’s heartening to hear that he’s been home-schooling his kids and is on a quarantine diet. This has helped him achieve a mythical status an artist who is difficult to pin down both musically and, after ditching his mobile phone years ago, physically. Sometimes, he says, he can be in his studio for three days straight with no sleep. He rarely gives interviews, presumably because they take up precious time: he’s laidback, but you can practically hear his toe tapping as he waits to hang up the receiver and get back to making music. The producer is as careful with words as he is with samples. “I always tag my homies when I feel something,” he adds. But he says that, to some extent, he feels a duty to keep his friend’s musical legacy alive – Sound Ancestors, for example, has a track called Two for 2 – For Dilla. He stopped writing rhymes after Dilla’s death, as he had done on their Champion Sound album in 2003, going on to explore other ideas such as his one-man jazz band Yesterday’s New Quintet. With the help of his father, a former soul singer, Jackson signed his first rap trio Lootpack to the Stones Throw label, then launched his alter ego Quasimoto, where he would rap in a pitched-up voice, practically unrecognisable. One’s a Blood, one’s a Crip.” He retreated into music from a young age, a self-described “black hermit” who studied his family’s record collections and spliced them into new shapes using a drum machine and a sampler. A lot of gang-banging, cousins fighting and killing each other. “I’m from Oxnard, there’s death all around. Partly it was the deaths of Dilla and his mother, a pianist who wrote his father’s songs, that motivated Jackson to work harder, he says, but really he’s had that mentality ever since his childhood in a rough part of the coastal town west of LA. He’s following that with new album Sound Ancestors, an instrumental listening experience arranged by electronic musician Kieran Hebden, AKA Four Tet, that is more in line with Boards of Canada. His last record was 2019’s Bandana, with Indiana rapper Freddie Gibbs, the second of their widescreen gangsta rap outings, which stood tall in quality and energy above anything else that year. But every time it looks as if he might nudge the mainstream, he’ll release something unexpected. That is why he’s still the go-to guy for a unique instrumental, the currency of hip-hop production: just ask Kanye West, Erykah Badu, Mos Def or, recently, poet, artist and activist Noname. The Wire magazine likened him to a “music librarian … the guardian of yesterday for the music lovers of tomorrow”. They feverishly flip through genres and grab loops from rarities (he is said to have over four rooms’ worth of them) like he’s making the ultimate musical scrapbook, meandering from Brazilian jazz to African funk to Throbbing Gristle. The 47-year-old is known for being immensely prolific: his discography is dizzying, with dozens of albums (as himself, alias Beat Konducta, Madlib Medicine Show, for other people, or collaborations). He isn’t one to pause much for reflection. Speaking to this somewhat, his new album starts with a prelude called There Is No Time.

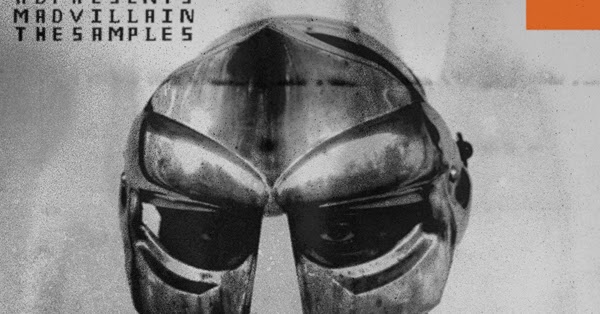

Jackson had previously likened Dilla to John Coltrane and Doom to Charlie Parker, two rebellious jazz greats, jokingly calling himself a Thelonious Monk now he’s the only one left of this holy trinity, the no-rules beat constructors who revitalised 00s hip-hop. It is not the first time Jackson has lost a friend and collaborator: his kindred spirit J Dilla, with whom he’d also made an album as “Jaylib”, died in 2006 aged 32 from rare blood disease TTP and lupus. “He was working hard on whatever he was doing. “But we said that every year, and it never happened,” he says. The last time they talked was “about a year ago” to discuss working on new music. That album is widely considered one of the greatest collaborations in hip-hop, two enigmatic minds whose disregard for form and embrace of experimentation inspired a generation of MCs. You might assume Jackson had a psychic hotline to Doom: as legend has it, they made their one album, 2004’s Madvillainy, in the same house without speaking, on magic mushrooms. “Last week I saw five of Doom’s albums on the top charts, and it’s sad to say but that wouldn’t happen if he was here.” He is glad his late contemporary is posthumously getting the recognition he deserves. “Everybody’s still learning off of him,” he adds. He described Doom as “a brother, a guy that took time to hang out, call me all the time” but also “king of the beats”, the “Muhammad Ali” of hip-hop whose rhyming skills are hugely influential.

“I still don’t believe it,” says the producer, real name Otis Jackson Jr, from his home in Los Angeles.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)